Voices: Sean Martinez of OpenOakland

OpenOakland’s volunteer contributors are the lifeblood of our brigade. We may have different backgrounds and experiences of our city but we’re united in our belief that technology can be a tool to empower communities and make government more representative of the people it serves. As we carry Oakland’s Pride Month celebration forward into our daily lives, we’d like to start introducing you to some of these members.

Today, we start with Sean Martinez, OpenOakland’s volunteer Treasurer/Recorder. Sean kindly sat down with Jess Sand, one of his co-leads, to talk about the unique perspective he brings to the brigade, the role of empathy in policy making, and the challenges—and joy—of learning and growing from a diverse community.

The interview has been edited for length and flow.

Jess: To start, why don’t you tell me a little bit about yourself outside of OpenOakland. What’s your background, what do you do? Who are you, Sean?

Sean: I’m a researcher. I’ve done research in health care and domestic violence. I originally started doing economic research. My parents were very adamant that I get an MBA at some point or get my Masters. And I decided, you know, what, I’m not going to do that at all, I’m going to do something for society for a little bit. So when I graduated college, I realized maybe I should work for a nonprofit. And I happily did for a few months! And then suddenly, 2016 happened and everything kind of fell apart. So I stuck around, continuing to do research and policy-making in the nonprofit field until now, where I now live in the East Bay and I feel really connected to a lot of organizations. But I still feel like I’m growing my connections elsewhere, and always learning. So it’s really exciting. And I always feel like I have something new to learn all the time.

It feels like everything was just an accident when I started. I didn’t mean to stay in the nonprofit world for as long as I did. I didn’t mean to do this kind of research and policymaking for this long. But I had way too much fun along the way, I met so many great people—incredible activists who really pushed my own thinking in terms of my own politics and my own understanding of what social justice really means. And I just kept going along for the ride.

Jess: You said you started off in research, in the domestic violence space and the justice space generally. Were those separate parts of your life that came together or did one lead to another?

Sean: It was more by accident. I wrote a couple of research papers touching on economic policymaking and city planning, and how that informs how we think about public safety and the kinds of tools that we use to create public safety. It made me realize that there are these other pieces of my own identity that help inform or gloss over things.

For example, I’m male-identified and designated male at birth. When I started doing that kind of research in the domestic violence space, I realized, wow, I don’t know what it’s like to be a woman walking through a parking garage at night. And I don’t know what kinds of things I would feel, or the things I would hear, or the things I would be concerned about. And that just creates my own blinders in terms of, what are the policies that I think are viable? Or what are the policies that are even relevant? And it really pushed me to get into other people’s shoes and really listen. And that was a really hard skill to learn when you’re a hotshot and you think you know everything because you have all this quantitative knowledge. You’re like, I don’t need your stories. I have data. But obviously that’s wrong. Pushing myself to be more empathetic and be more connected to others—that really made my work more nuanced. It made my work much more interesting.

Jess: Was there a particular incident or moment, or person, that got you there? Or was that something you evolved into? Because I don’t think of that as being a typical evolution in thinking. I mean, I think a lot of people in the research and policy world don’t necessarily end up there, with that empathetic mindset.

Sean: When I was in LA, I met a group who worked in Brentwood, the Pacific Palisades, and the area around it. I remember asking people, what is it like and who are the people that you serve? And they described a lot of women who were staying in their RV campers and who were fleeing their partners because they were victims of intimate partner violence. And that really struck me. Because my vision of a person who is living in an RV camper on the street was very much informed by class and maleness and even ableism around things like mental health. It didn’t register with me that there was this gender component.

And it really challenged me. Why did I not think about that? And it was in that process of being surprised, of interrogating my own self, that I really started to become less of an asshole and more of a well-rounded and more receptive person. And I think that in my own work now, that’s a hard line to balance, being able to make really broad recommendations in terms of policy, but then being able to thread the line and talk about nuance. And, you know, the better you are at recognizing that nuance, the harder it is to make really big claims about what the right policy is sometimes.

Jess: It’s interesting to hear you talk about discovering your own biases like that. I mean, you’re an Asian American working in the technology space and you’re also openly gay. So you have certain experiences that someone like me, as a straight, white woman, doesn’t have. Yet you’re very aware of your own positionality. Can you say more about how that awareness of your own position in relationship to others, and your own intersectional identity in particular, informs your work?

Sean: Going back a long time ago, when I first graduated, I was like, “yeah, I’m a hotshot, I understand everything.” But then getting checked on understanding that my own intersections are not other people’s intersections—that was really an important wake-up call for me. To realize I still have a lot to learn and other people have a lot to learn, too. And if I’m thinking about this, then how can I help other people think through this, too?

My own experiences have given me this feeling—an instinct—when feeling out these questions of, like, what should we be doing? How should we address this question? What are the policy implications? And just honing in on those instincts or recognizing that there is something there.

My experiences are very different than another Asian American person’s experience or another gay person’s experience. But recognizing that there is some sort of instinct that says, “Wait a second, they’re saying something that feels similar to something I kinda know about. I wonder what that is about?” Or, “Someone is saying something different; I wonder where that’s coming from and how that might affect or shape their understanding?”

For me, having that intersectional identity and those instincts has only made me want to bring that instinct out of other people, too. Because if I can help other people have that sense of, you know, “this person is bringing up a theme that I am not really familiar with”—I want them to own that and say, “I want to dive into that deeper,” or “I want to figure that out or learn more about that.”

I think in our work, we need to be doing that all the time. It’s hard because that instinct can be buried by a lot of things. We try to be empirical about things or overly scientific about things. Or maybe it’s just really uncomfortable. But my job has been to let people say, “you know, this is interesting. And I don’t know what’s going on here but I want to keep the conversation going.”

Jess: What does that look like in practice?

Sean: I think it means letting other people fall down and pick themselves up. For example, there was a time some of us on the Open Budget team had some really differing opinions about what policing should look like in Oakland. What is the responsibility of the police? And how should that be rolled out in the budget? And everyone was operating at different levels, or different perspectives. I could just go in and tell people what to think, or I can let other people figure it out for themselves.

And that meant building in safe spaces to have those conversations. It meant me reaching out to people one on one, and asking them how they feel. And maybe presenting them with different resources, differing perspectives, or supporting evidence. But it also meant just sitting back and being a fly on the wall to watch the conversation unfold.

As a result, there was a very nuanced discussion in Open Budget. People were able to really see not just traditional versions of identity such as race, class and gender, but they were able to see new versions of identity such as, what neighborhood are you from? What age are you? What is your able-bodied status? What has your experience been with the police before? And these differing perspectives, these different intersections of one’s experience, have really taught others to be more nuanced and be more thoughtful. And I think, as a result, people are really having complicated opinions, and I love that.

Jess: So, talk to me a little bit about the work that you do now and how you bring that in?

Sean: Yeah, so a lot of my research is about class and technically, it’s about efficiency and operations. You know, how do we deliver services and impact to the community in the most efficient way? Back at my previous organization, which was healthcare, we served hundreds and even thousands of people across three, sometimes even four, counties. So the questions I was faced with at the time informed by service capacity. But at the core of it, it’s really about, how do we meet people where they’re at, given certain constraints or given certain issues that they face.

For example, a classic problem is how should we best serve a community that is mostly rural when we only have a single two-hour block of time to meet them; what’s the best time? What’s the best day? And that’s not really about operations and logistics. That’s really asking, do you understand the community? Do you understand the people that you serve? Do you understand their needs and their challenges? And can we work ourselves around that?

I think in that way, my research has really pushed me to think really strategically about how to understand the community. How to understand the people that we serve. How do I think about this community in a way that I’ve never thought about? You know, thinking about the people that you serve means that you just have to know who they are and put a face to who they are. And that can be really hard when we’re thinking so abstractly.

Jess: Are there particular techniques or methods you use to understand the people that you’re developing and describing policies for?

Sean: These questions about policies are really about stories—and how we tell those stories. Sometimes it makes sense to tell it as a really personal, one-to-one story where you’re narrating the issues of one family or a single person, and talking through the opportunities and the disadvantages that we need to tap into or observe so we can make a more informed decision. Other times, it’s about data and, you know, presenting the best chart.

So while I always think about the data, where I really begin is centering myself around the problem or the person. And that really pushes me to think about the kinds of people that we serve, the trends in the population that are emerging, the issues that they are thinking about, that are slowly coming to the surface.

COVID-19 has taught us everything is political. From childcare to gas prices, everything is policy. And so how do we recognize those elements, and then understand the dimensions of the community and start to unspool that? Or start to work around that? It’s really complicated, but I think that if you’re creative or you’re ambitious—and you’re empathetic—then you’re inclined that way anyway.

Jess: So how do you humanize the people you’re trying to serve? How do you wrap your head around those different populations and move beyond the abstract?

Sean: I am a cheater! My first thing I usually do is I just ask other people or read into what other people are doing. Because I know I’m not the first person to think about this. So I start by understanding the breadth of the literature at large and thinking pretty strategically. Then I start digging a little deeper: like, tell me about the story of this community. Or, there’s this community that seems really invested and has a large proportion of donors or volunteers—tell me what’s going on over there. And as I started digging deeper and deeper, I started seeing a lot of contours and nuance. There are a lot of gradients to the question now. As I start seeing the trends, I can start to see something that is challenging my perspective.

But even as I get closer and closer to an answer that I feel confident in, I realize there are always going to be questions that I personally don’t have the answers to just yet. I remember a mentor saying, your job isn’t to get the right answer, it’s to get the best answer [given what you know]. And, you know, sometimes in our work and in social justice more broadly, that doesn’t seem fair or it doesn’t seem okay. Because your best isn’t necessarily enough. But, you know, that’s sometimes the only way that you can keep moving the ball. And that’s really important.

Jess: That’s a really meaningful way to look at it; this idea that you’re drawing on multiple kinds of data. So that might mean a broader literature review or audit of existing information and at the same time, you’re bringing in primary data, like quantitative surveys. And then you’re actually talking to people and bringing in those lived experiences through qualitative data. And all of that shapes the picture you’re developing. It points to this idea that there is no one objective reality. It all depends on what material you’re bringing in and who you’re talking to. And being able to do that in a thoughtful and intentional way, to make sure you get that breadth and that diversity of perspective is just really powerful.

Sean: Yeah, I think that’s kind of what drew me to OpenOakland. You know, very rarely do normal people get to have a chance at talking about policy in this really meaningful way. Like you know, improving services, or directly making an impact on policy making or helping partners shape the community around them, whether it’s visualizing some data or making a service really available to the community.

Because in this kind of work, there’s always going to be someone who’s left out of the conversation. I’ve seen this happen a lot in terms of affordable housing, for example. There’s always going to be someone who isn’t at the table, because it’s just too hard to think about, or it’s too complicated, or we don’t have enough time or money to bring them to the table. And so you kind of get what you get and you just accept the cost.

But here at OpenOakland, we can say, “no, that’s not okay.” We can keep on going. We can push ourselves and if we really push ourselves, then the vision that we have, in terms of serving the community, is so much more ambitious then what we originally started with. And even though we may not be perfect in terms of serving the community, we got the ball rolling. And because we’re open source, someone can fork this project and make it a little better in their own iteration. Or maybe someone can roll out another version for their own community elsewhere in the United States or across the globe. Or maybe someone will look at this and say, I have an improvement or something that I want to add, and they can commit that to the branch and grow it in a certain way. So I think this is really fun work that I get to be a part of at OpenOakland, and you’re so close to the action, why wouldn’t you want to be part of it?

Jess: So what made you decide to go even further and become a co-lead of the brigade?

Sean: I think it really came down to the fact that I felt there was something that OpenOakland really was lacking. I wanted to give it a policy focus—that understanding that it’s not developers that drive our work, it’s that the work drives our work. It’s the mission that drives our work. It’s the people that drive our work. And I think, in a way, it somehow—it’s not that it got lost, it’s just that the focus shifted for a little bit. And I wanted to bring it back. I wanted to highlight it in a real way. And really make people, if not uncomfortable, make people really realize that this is important. And this is really hard.

Jess: That kind of goes back to what you were saying about drawing on different experiences to inform our sense of reality or perspective. This idea that we have this opportunity to surface the gaps and the challenges and the inequities. As well as contextualize them by helping people understand the policymaking that has resulted in these outcomes. That policymaking, like you said, is not neutral, and that the presentation of how we shape these understandings is not neutral. And so our role as technologists, as producers, calls for a real self-awareness. What’s your sense of the brigade’s experience of that, as a collective of a lot of different kinds of people, working through that understanding?

Sean: Sometimes when you have complicated opinions, it’s really hard to articulate that in a way that doesn’t make people immediately angry. For example, I have a really complicated opinion about how cities should be funded, or how our revenue strategy should be structured. And it might make some people freak out. Like, I think the infinite cycle of going to voters year after year to authorize city bonds for schools are a distraction from funding our schools appropriately. And the gut reaction from people would be like, you don’t care about our school system, you don’t want us to have the new pool building or prom night, how dare you! But in reality, once that fire simmers down, then I can say, okay, what do you think is the responsibility of our government? What do you think is the responsibility of consumers? How do you think we should be funding these services the government provides? Do you think certain people should be exempt from paying for these basic services that the community uses, or that some people use but other people don’t?

And when I have that more deep and nuanced conversation, people start to really peel back and say, oh, I’ve never thought about that. Or you’re right, a soda tax really is just a child tax because children and families are some of the largest consumers for sodas. Or paying for groceries, like a one-cent tax on every dollar at the grocery is actually an unprogressive tax on poor people to pay for the school system because the more money you take home, the less of a burden this particular tax is on you. And so these conversations that I have about these really complicated topics are broader conversations about how you think about your place in the world. How do you think we should serve our community? What is the scope of our government services? And where do you think you should plug in?

Those conversations are harder and much longer. And I think here at OpenOakland, my job is to be there, as at many points in the conversation so that people can show how they’re growing or say, “I’m struggling with this,” and I can give them something so they can continue their journey. It would be cool if people had the same opinions as I did. But I think the more interesting thing is for someone else to come up with their own ideas. Then we work together, because they contribute something that I don’t have, which is their voice and their experience and their thoughts.

Jess: So as we wrap up this conversation, we’ve also just wrapped up Pride Month. And there’s multiplicity and plurality within each of these communities and across these communities—as you touched on earlier, your experience as a gay man is not every gay man’s experience. So as our volunteers try to answer some of these tougher questions and create this space where we’re all able to show up and explore our city’s needs and opportunities together, is there anything in particular you hope to see in that space?

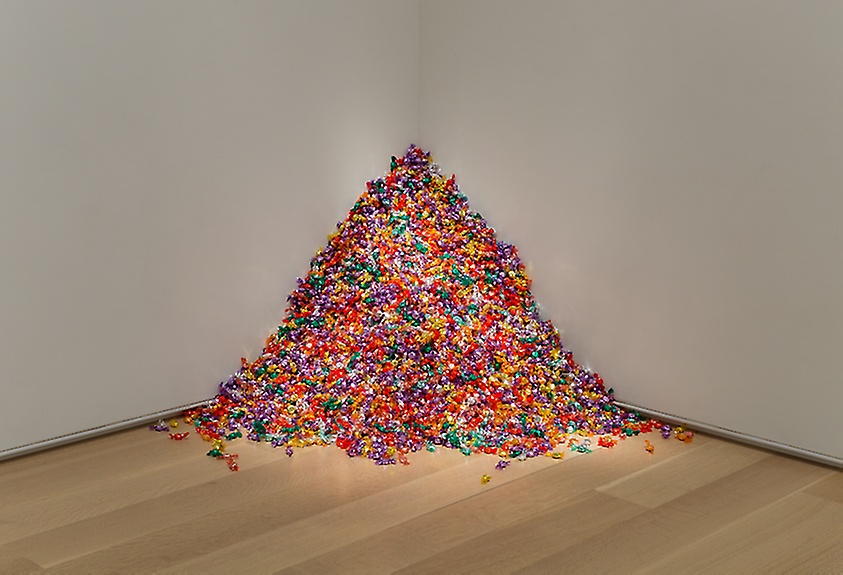

Sean: Yeah, so every year I think about this piece of art, “Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.),” by Felix Gonzalez-Torres. It’s basically a pile of candies in the corner of a room. Anyone can make this art; the only rule is that it has to be exactly 175 pounds of candy. And it encourages people to pick up the candy and eat it. I remember seeing this piece for the first time and I remember thinking, anyone can experience this. Anyone can take a piece of candy off of the pile but each person is going to experience it differently. A kid is probably just going to enjoy the candy for what it is, but someone who knows the story of this or who has a family member who was touched by AIDS, or someone who has been working in this space, or someone who just came out—they are going to have a radically different experience, even though they’re all doing the same thing, which is observing and eating.

And to me, you know, that is really kind of what I’m doing in my work. And what we’re all doing. We’re all looking at this big universe of data, this big universe of information and trying to make sense of it. And we’re all getting something different. But when we start realizing that our experiences are connected to something and we can share that experience with each other, that’s where some real magic happens. This piece of art reminds me that Pride is so much more than just activism.

It’s about giving us space to be our human selves, our full selves. And when I look at the people at OpenOakland who may be celebrating Pride, or maybe are just there on the sidelines, you know, they’re part of that, too. They are giving everyone in this space the chance to tell their stories, to live their full human life and to be who they are. And sometimes that’s challenging because, you know, we have to acknowledge that there’s significant political challenges or policy issues that still need resolving. But giving people the space to exist means that we’re not glossing over them, we’re not letting them be in the shadows. We’re putting them in the light, the foreground, and saying, we’re gonna do something about it. And for me, that’s probably the most exciting part of Pride— that you get to see people be who they are. And if we’re lucky, we get to have fun while doing that.

Perspectives expressed in the Voices series are that of individuals and do not necessarily reflect that of OpenOakland membership at large. Want to see someone featured? Submit a suggestion.