RADAR Program Exploration: Learnings from a Discovery Phase

Last year, several OpenOakland members kicked off a discovery phase for a potential service delivery program to serve local nonprofits. We were looking for ways to reduce project overhead while centering the specific needs of local community groups. Inspired by BetaNYC’s Research and Data Assistance Request (RADAR) initiative, we wondered if something similar might work here in Oakland. Despite wrapping up our discovery phase early due to pandemic life, we wanted to capture our initial learnings here.

Jump to:

Video recap | Slide deck

TL;DR:

- We wanted to explore if a program specifically aimed at increasing our impact through low-overhead projects might solve some ongoing brigade challenges, including serving Oakland communities more effectively and providing volunteers with a more meaningful experience.

- We found that a program like this would help us make projects more systematic and benefit existing teams.

- The program model itself may or may not be useful to Oakland nonprofits. Understanding these organizations and their specific needs is mission-critical for a successful program.

- Certain building blocks that we don’t yet have would need to be built out for this to work (tools and templates, defined roles and processes, a volunteer management system).

Why explore a program like this?

Over the past several years, OpenOakland has taken on new projects in an ad hoc way, with little formal methodology for selecting which projects to invest our volunteer and financial resources in. Many of these projects come directly from regular OpenOakland members, or as requests from local nonprofits and city agencies or staff who have heard of the brigade and wonder if we can help with a specific need.

While this method of intaking new projects may seem organic, it limits our impact to those already within our orbit, which can mean we’re mainly exposed to ideas from within our existing professional and social networks. We wanted to explore if a RADAR-like program might be a good fit for addressing some of our challenges at OpenOakland. Designing a program specifically aimed at increasing our impact through low-overhead projects could have a multitude of benefits. It has the potential to:

- Focus our project portfolio around community-initiated needs from a wider variety of community groups.

- Scope down our projects so they’re smaller and more deliverable.

- Create a more structured project scoping process to help volunteers plug in more easily.

Defining our discovery process

We knew from the outset that we would focus our discovery phase on understanding the need among our potential clientele, and the constraints and opportunities facing the brigade. We did not intend to actually design a program. This approach was based on OpenOakland’s evolving project life cycle.

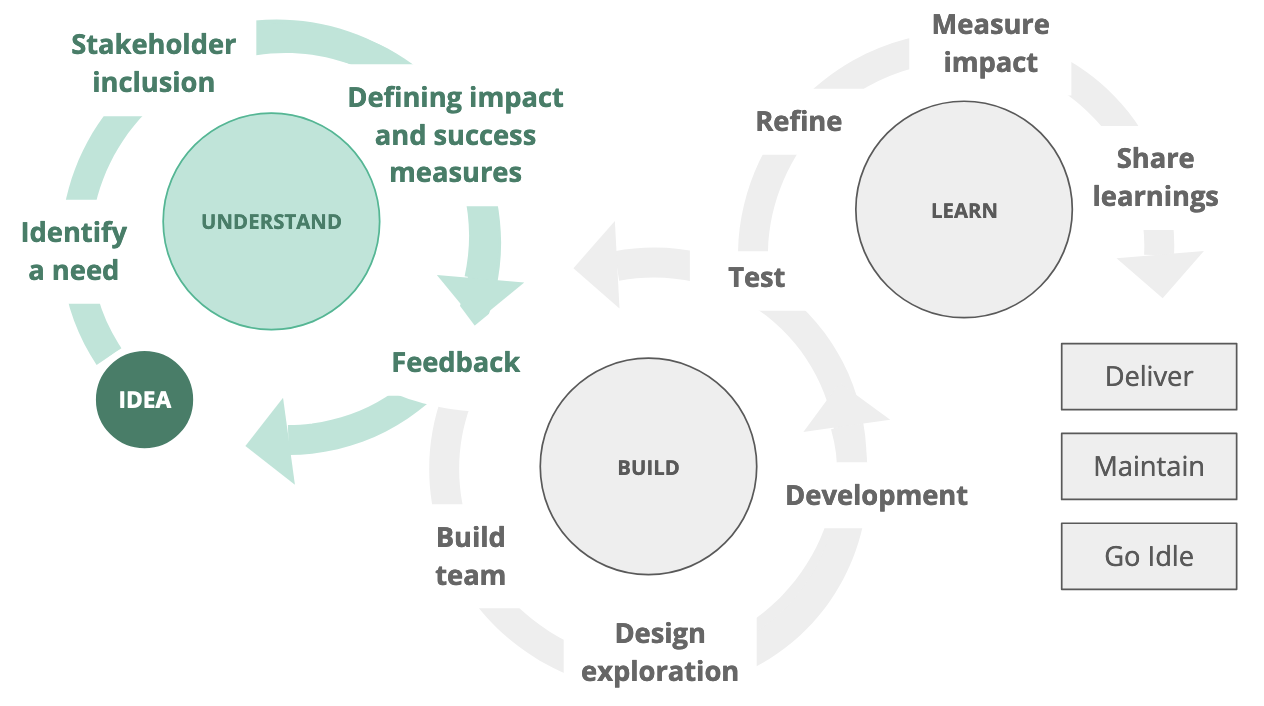

Our project life cycle is an aspirational approach to designing community-rooted technology solutions. It consists of a series of cyclical phases that can scale up or down depending on the individual project. It’s designed to build in key steps and milestones that support community engagement, ongoing learning, and open, transparent communication.

Parallel learning paths

As we started gathering information and developing questions, we quickly noticed three parallel learning paths:

- Outer circle: Community needs beyond OpenOakland

- Center circle: Brigade strategy (how and why we do what we do)

- Inner circle: Program design and logistics

How do we validate an idea?

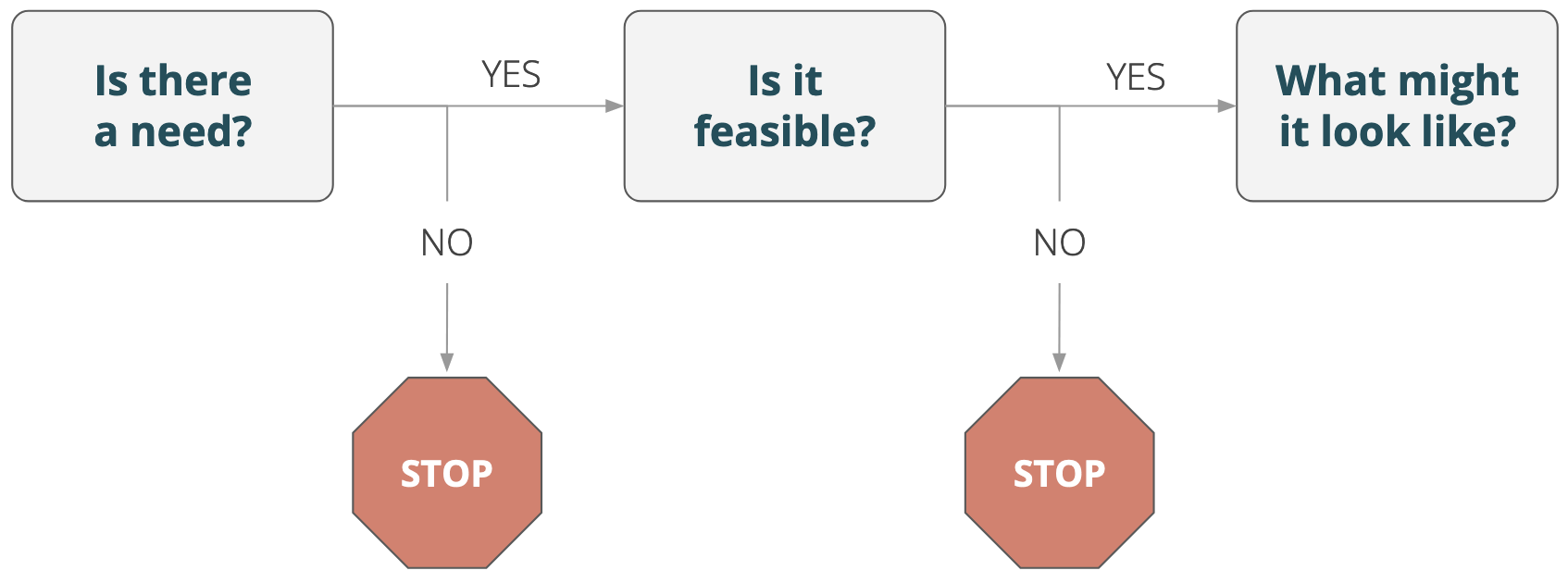

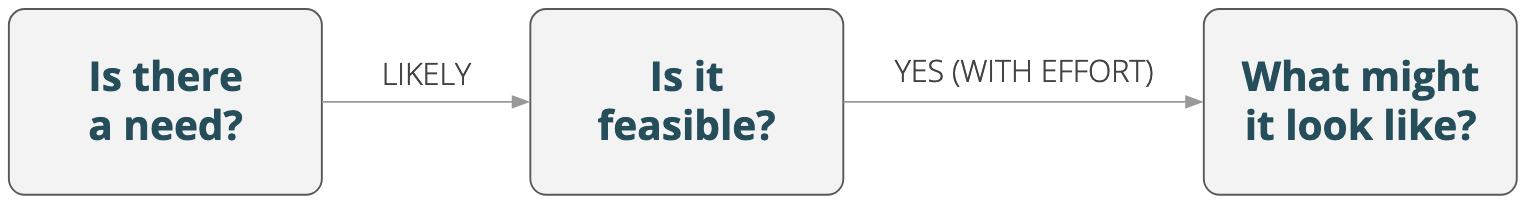

Given the limited capacity of our discovery team, we knew we needed to answer some mission-critical questions while expending the least amount of time and energy possible. We used a stop/go framework to determine whether or not to move forward at each learning juncture.

We intended to start by identifying whether there was an actual need by doing an initial round of informational interviews. This research would give us a better understanding of those community needs, so we could then determine if OpenOakland has the appropriate resources to help fill those needs. If not, we could stop pursuing an unnecessary solution and redirect our energy elsewhere.

Our hypothesis was that we might find a greater need for tech infrastructure and data management skills than more sophisticated data analysis and presentation/advocacy needs. We also guessed we would need a more robust recruiting strategy and volunteer management system than we have now (spoiler alert: we were right).

Only once we determined that a program like this was both valuable and feasible would we begin designing it. This keeps us from over-investing volunteer resources in something that may not be a meaningful solution.

What the process actually looked like

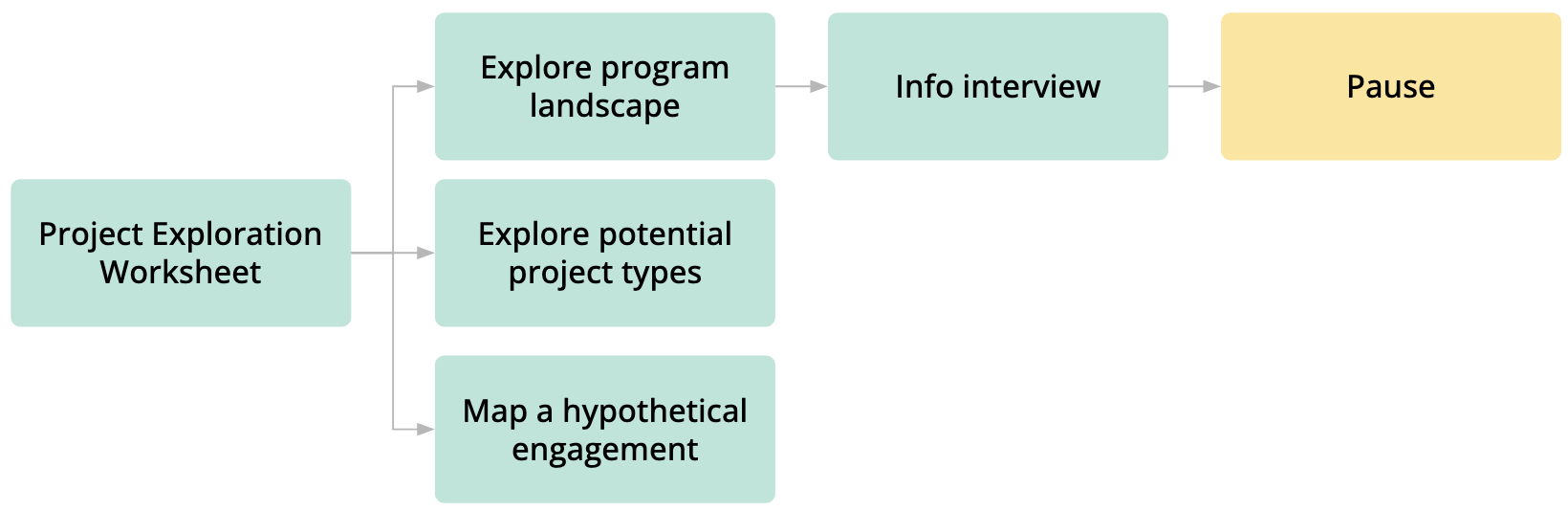

Like all project ideas at OpenOakland, we started by filling out a Project Exploration Worksheet to start defining stakeholders and understand some of the broader implications. From there, we drafted an outreach and interview plan. To do that, though, we needed to define exactly who we wanted to talk to.

This proved more challenging than it would seem. We had capacity for 4-6 one-hour conversations. We decided to try to speak to a mix of direct service and advocacy organizations across a variety of causes.

As we were trying to target the research plan, we did some additional due diligence:

- We reached out to BetaNYC to understand how they manage their program, lessons learned, etc.

- We sketched out different kinds of data projects that organizations might potentially need.

- We broke down a rough project journey to get a sense of the kinds of resources and processes we might need to address.

At times it felt like we were getting ahead of ourselves, considering we hadn’t yet spoken with any organizations in our potential target clientele. But our small team, with limited capacity, had trouble scoping that outreach process without a larger brigade service strategy in place (more on this shortly). We ended up working where we felt most capable and documenting the unknowns along the way.

Brigade strategy takeaways

Even in the short time we were actively exploring a potential RADAR program, we learned a ton.

Developing a successful program would benefit existing project teams

The building blocks needed for a program that turns out smaller projects more frequently (such as tools and templates) could be adopted and adapted by other project teams. This would make the program scalable more easily, for potentially greater impact.

Without a brigade impact strategy, a self-contained program will be challenging

Decisions about execution require a point of view on who we actually want to serve and what kind of impact we expect to make. This has been a long-standing issue for OpenOakland, where we often want to be “all inclusive” to the point of never saying no to anything. But inclusivity doesn’t necessarily mean trying to serve everyone. Casting too wide a net may actually dilute our impact, make a program like this less effective, or worse: waste our volunteers’ and partners’ time and resources on a less successful project.

We need a better shared understanding of the nonprofit landscape in Oakland

There are approximately 3,750+ nonprofits in Oakland (Source: ProPublica Nonprofit Explorer). Who gets funding and from where? Which causes are underrepresented? How digitally mature are these organizations? How do they use data and technology now? How are they staffed? What do they struggle with? Understanding this can help us focus on where the need is greatest and/or where OpenOakland can be most useful.

Guidance for exploratory research would be helpful for solving existing brigade knowledge gaps

Scoping templates, training and guidance would make it much easier for non-expert volunteers to shape the discovery process. Our team learned this first-hand as we struggled to narrow our research scope. Filling this gap would make us much more effective at one the most critical stages of an OpenOakland project: needs discovery.

Project management takeaways

At a more tactical level, we surfaced a number of important learnings specific to how projects might be managed.

For a low-overhead engagement, we’d need specific elements in place

This is one of the most frequently recurring needs across the brigade generally and a great example of how a formal program built around structured delivery can benefit project teams, as mentioned earlier. Critical elements include:

- Templates, checklists, starter packages

- Defined workflows

- Recruiting pipeline and infrastructure

- Documented role descriptions

- Clear program positioning

Teams need a process for identifying stakeholders

It’s not enough to ask project teams to engage stakeholders if they have trouble defining who those stakeholders might be (we don’t know what we don’t know).

Customization needs can be a signal the project isn’t a good fit

Incoming requests aren’t always predictable. Projects that can’t be handled by existing templates/processes should be re-routed, instead of over-investing our limited resources on customization.

Scoping should include more than just a tech deliverable

Will our open source philosophy conflict with our partners’ usage needs? (How) do we ensure projects are used for their intended purpose? What agreements will OpenOakland make with our project partners around usage and communications?

Projects need to be scoped into chunks Creating clearly-defined phases that can be quickly completed by a small number of people keeps momentum going and helps volunteers plug in without too much onboarding (like a relay race).

Community partner takeaways

Our team’s biggest regret was not having capacity to complete this stage of the research. As with many volunteer projects, we had to pause to make space for pandemic life. Yet we still learned a good deal from the exploration we did do.

Different types of organizational needs have different impacts and implications for project collaboration

- Capacity needs: Data management/architecture

- Strategy needs: Research and analysis

- Advocacy needs: Data storytelling

Partner characteristics will likely impact how we deliver services

- Tech maturity: Means less hand-holding

- Smaller staff: Results in limited time availability

- Historically marginalized groups: May need more trust-building

- Etc.

We need a better way of managing partner contacts/relationships

We don’t have shared ownership of relationships across brigade members. It would be helpful to have an up-to-date roster of past partners and key contacts for early outreach, as well as a larger list of potential partners.

What could go wrong?

OpenOakland’s project exploration worksheet helped us consider potential harms the program might cause if implemented poorly or unintentionally. Identifying these risks allowed us to then consider ways to mitigate these problematic outcomes.

Designing for, not with

Perhaps the most significant risk this program poses lies in its very structure. A model in which an organization comes to OO with a well-defined request and OO does the bulk of project decision-making reinforces a lopsided power dynamic. If we want to build power among underrepresented communities in Oakland, then our processes need to reflect that authentically. Does a program like this actually do that? This question still needs to be answered. One way to mitigate this might be to invite potential partners into the program design itself.

Other risks include:

- Not enough program interest

- Not enough volunteers to support requests

- Failure to say no or scope down

- Unclear ownerships (open source vs proprietary)

- Other unintended consequences (unethical or inaccurate uses of our work)

The solution to each of these depends on its root cause, so more effort here is definitely needed.

Recommendations for next steps

Should OpenOakland choose to revive a RADAR exploration process, our team recommends beginning with some basic due diligence.

- Do the community research.

- Create an impact measurement plan.

- Build some basic tools.

- Run a pilot.

1. Do the community research

Our recommendation is to start with a round of informational interviews or open-ended listening sessions using the draft research plan as a starting point. Using the learnings from the qualitative round, we would then recommend a quantitative survey of Oakland nonprofits to understand how representative these needs are among the wider community.

Questions to explore:

- Is our initial estimate of project types needed by organizations accurate?

- What other tech/data needs do organizations have?

- How common is each need for organizations?

- How urgent is each need for organizations?

- Is need impacted by org type, structure, budget, (tech/data)maturity, size, cause?

2. Create an impact measurement plan

Our team strongly recommends not proceeding without an impact measurement plan. Starting with the broad organizational outcomes we want see, we can then ladder down to identify the indicators for those outcomes and finally, the specific metrics needed to inform those indicators. This approach borrows from Oakland’s Dept. of Race & Equity presentation on results-based accountability.

How much did we do?

- What kinds of orgs?

- Project type breakdown

- How many requests fielded?

- How many orgs served?

How well did we do?

- Project exposure/adoption (need metrics)

- Satisfaction rating (OO volunteers)

- Satisfaction rating (partners)

Was anyone better off?

- Increase in partners who know how to do XYZ with technology or data

The indicators for measuring “was anyone better off” are largely dependent on what needs we end up trying to fulfill.

3. Build some basic tools

Even a small pilot program will require pre-built infrastructure (the purpose of a pilot is to measure whether an off-the-shelf program can be successful (emphasis on off-the-shelf).

Tool creation should be based on what kind of projects we want to focus on first and should result in a “kit” for project teams that includes processes, roles, templates and reproducible starter components.

4. Run a pilot

- Develop the specific resources for 1-2 priority project types based on the first round of research.

- Promote the pilot to the target clientele.

- Evaluate incoming requests for project and organizational fit.

- Assemble the volunteer team and deliver the project following the predefined process.

- Evaluate at major milestones, adjust, or stop.

In summary

A program like this would help us make projects more systematic and would benefit existing teams. The program model itself may or may not be useful to Oakland nonprofits. Understanding these organizations and their specific needs is mission-critical for a successful program. Certain building blocks that we don’t yet have would need to be built out for this to work (tools and templates, defined roles and processes, a volunteer management system).

Watch the presentation

View the slides

Acknowledgements

OpenOakland is grateful in particular to volunteers Angela K. and Joyce L., who supported this work. We’re also grateful to the BetaNYC team, who generously shared their time and experiences with us.